When I sat down with Mabel Slattery to record the latest Court Jester episode, I expected a story (I got one), a lot of laughter (tick), and maybe a few surprising insights (tick again). What I didn’t necessarily expect was to dive into the deep end of the questions I’ve been asked the most for years:

“Were We Always Laughing at the Same Things?”

Or: “How Are We Still Laughing About This?”

Or: “You couldn’t get away with that today.”

Closely followed by: “You can’t joke about anything these days.”

Then I tell them that in the 13th century, someone wrote a story where the Devil creates the vagina with a garden spade and farts into a woman’s mouth. So yes, medieval people joked about everything, and so do we.

But here’s where it gets interesting: how do we joke? What do we find funny, what crosses a line, what causes an eyeroll (today) or a public flogging (thankfully no longer a legal response to a bad joke)?

If you’ve ever read a medieval fabliau (or heard me tell it) and thought “Was I supposed to laugh at that?”, congratulations: you’ve opened the gates of humour theory.

Let’s break it down. Here are the four core theories of humour.

Superiority Theory

This is the oldest one, advanced by Aristotle. Predictably, it’s also the most smug. The idea is that we laugh because we feel superior to someone else: the foolish, the ugly, the disabled, the cuckolded husband trying to outwit his wife and failing gloriously. We laugh at those less fortunate than us. We laugh because someone else looks ridiculous, and we feel better about ourselves by comparison.

Superiority humour is why we laugh at Mr. Bean, the boss in The Office, and every banana peel moment on TikTok.

Relief Theory

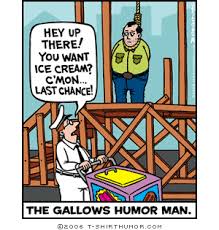

We have Freud to thank for that, and it’s the only one of his theories that has not been debunked, so he may have been on to something. Freud suggests that laughter is a kind of release: of tension, of repressed desire, of social or sexual energy. It’s what happens when we let something out that’s been sitting too tight.

Think Fleabag, where jokes around grief, trauma, sex and shame make you wince and laugh at the same time. Gallows humour also thrives here: “Well, at least I’ll never have to file taxes again,” says the guy on death row.

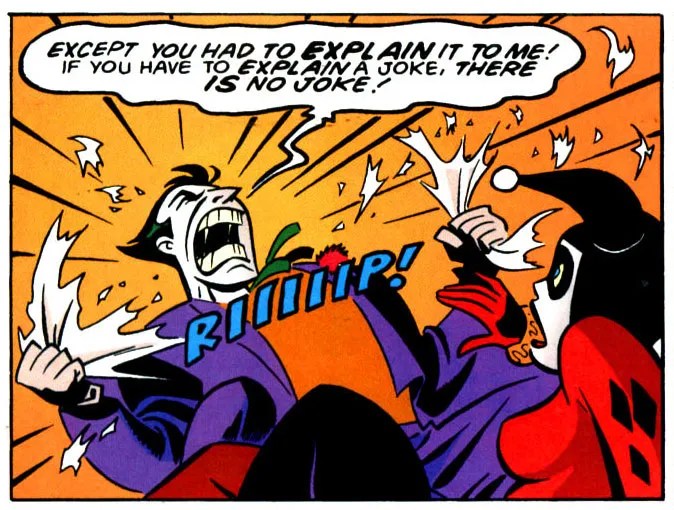

Incongruity Theory

This one is the academic darling. It claims that humour comes from the unexpected, the moment when logic, context or narrative gets interrupted. It’s a pattern-breaker.

Think of the Monty Python knight who gets all his limbs chopped off and still insists it’s “just a flesh wound.” Absurd. Incongruous. Hilarious.

Incongruity surprises you, relief soothes you. Which leads us to…

Benign Violation Theory

My personal favourite. This one says humour happens when something violates our norms (much like the previous one) but in a way that feels safe. It’s like a misstep that doesn’t quite trip us up. If the violation is not safe, we’ll understand it as a threat, and we’ll be offended, angry, defensive…we’ll be a lot of things, but we won’t be laughing.

Think of every “Too soon?” joke you’ve ever heard. Or of every political satire, that holds the politicians in question to the same moral standards that you do.

I love this one because it goes heavy on the audience. Different audiences will respond differently to the same joke, because what feels “benign” to one group might feel like a “violation” to another. Try telling a misogynist joke in a feminist convention and see how that works for you.

Duh, I hear you say. But stay with me, this will be important in a minute.

So…are we still laughing about this?

If you’ve read this far, you probably figured out that most jokes a combination of the above, sometimes all at once. The same is true for medieval humour. Cuckold jokes? Check. Religious satire? Check. A woman convincing her husband that he is dead and should stay covered in a shroud while she has sex with her lover (who is also a priest) next to him? Check.

The structures have always worked, so yes, in a way, we have always been laughing at the same things. When I read a 700-year-old joke about lazy peasants, horny monks, cuckolded husbands and frisky wives, I don’t just laugh. I see continuity.

The fact that we can still get some of the fabliaux humour means something. It means that we are operating under similar social norms, enough for us to understand the violation and not be threatened by it.

Some of those jokes fall flat today. They cause a cringe, not a laugh (especially if the audience thinks I am telling them a joke I just came up with, and not a centuries-old tale). The fact that I need a paragraph of content warnings each time means something, too. It means that some of the older social norms have shifted.

And some of those jokes are still funny to some, and appalling to others. This also means something. It means that we are, once more, in a moment of cultural transition.

Boundaries aren’t signs of humour dying. They are an indication of its constant arm-wrestling with shifting social norms. They’re signs of awareness growing, of societies changing. So if your punchline crosses boundaries, expect to be called on it, and maybe write a better joke next time.

“You can’t joke about anything these days”

Of course you can. You can joke about everything you like, but that doesn’t mean everyone will laugh. At the end of the day, this is what determines a good joke: people laugh with it.

And bad jokes exist. That doesn’t mean you’re being silenced. It means jokes, like everything else, exist in a living cultural ecosystem. If your punchline offends your audience, people won’t laugh. That’s how humour works. You may not like it, or not agree with your audience, but that’s a different discussion entirely. For a different post, maybe (makes note for next time).

Humour has always inspired strong emotional reactions. It still does. I could tell you that in the Middle Ages the wrong joke could get you executed, but we don’t even have to go that far back in time for that.

Why it matters

If you know how to read it, humour will tell you what the real power structure is. It’s not a coincidence that in the fabliaux you will find loads of jokes about the lower clergy, but not many about the Pope. We laugh at those close to us, not at those with enough power to do us real harm. The details of how power structures exist within humour and whether humour challenges or enforces the status quo are a post for another day (makes more notes for next time).

Humour will tell you what a society fears, desires, and desperately wants to pretend isn’t true. It’s not about what you’re allowed to joke about. It’s about who’s laughing, and why. That’s why I study medieval humour: to listen.

Want more?

The conversation that inspired all this will be on Patreon this month, and more musings on medieval humour will continue here, probably without much of a plan.

I’d give you a bibliography, but it’d be longer than this post. So if you want to talk books on humour and laughter, drop me a line.

And if you haven’t already, you can catch the stories on The Court Jester podcast, or follow the blog via email and you’ll be added to the newsletter, for more para-academic folly in your inbox.

Leave a comment