My body is back on my desk and my mind is deep in medieval France, and in these community rituals that use humour and derision for social regulation. Today we are exploring misrule and how it is recruited to enforce the rule, punish transgression and exact revenge on sins against marriage: actual marriage, prospective marriage and past marriage.

Allow me to introduce you to the raucous mayhem that is the charivari.

A Headache with Etymology

If you’ve ever seen an american film when the newlyweds drive off towards the sunset with cans banging after their car, you have seen what may be the remains of the old custom. Charivari means noise, cacophony, headache. We think that the word comes from either Latin or Greek, but either way, the etymology seems to point to either a heavy head or a loud noise, that would probably cause a heavy head anyway.

Community rituals to punish wrongdoing with loud noise and slapstick humour also exist elsewhere, but in medieval France charivari had a particular flavour: it was mostly used for transgressions against marriage and to regulate sexual, and therefore marital and extramarital pairings.

So, in the fourteenth century we have adulterers punished by ducking in the village of Laleu. Husbands were paraded riding a donkey backwards in Senlis because they had been victims of domestic violence: they had been beaten by their wives, which was unacceptable. Most frequently, charivaris would be held “against” second marriages, when a widow or a widower was getting remarried. Mind you, this practice was no longer against church law, or socially frowned upon, but there were specific groups of people who had really strong opinions on the matter.

And it may surprise you to find out that these people were, largely, young unmarried men.

Incel, but make it medieval

From the twelfth century onwards, we find throughout France organised groups of young men of marriageable age. We don’t know how a person joined one of these groups, but we do know that at the time, men would not marry until their early to mid-twenties. Being single and full of teenage energy, these boys gave themselves a series of responsibilities in the community: from organising and presiding in festivals, to policing the behaviour of married and unmarried people.

This is, for example, how we end up with organised games of married against unmarried men, that could get particularly violent. Youth groups also demanded a fine if an outsider showed up and courted one of the eligible girls of their community, and they would kick up a fuss on a couple’s wedding night, trying to teasingly prevent them from consummating the marriage. They’d plant a stinky bush in the yard of a girl whose morals were questionable, and punish marriages that have been infertile for too long.

It looks like the main reason behind all that was, to an extent, access to eligible marriage partners, which is why charivaris were particularly brutal against second marriages. The idea was that the person getting remarried is giving themselves a second chance, while also removing eligible candidates from the marriage market, when others haven’t had the opportunity to get married at all. Age difference was also a popular insult in these cases, possibly because such marriages were less likely to lead to children.

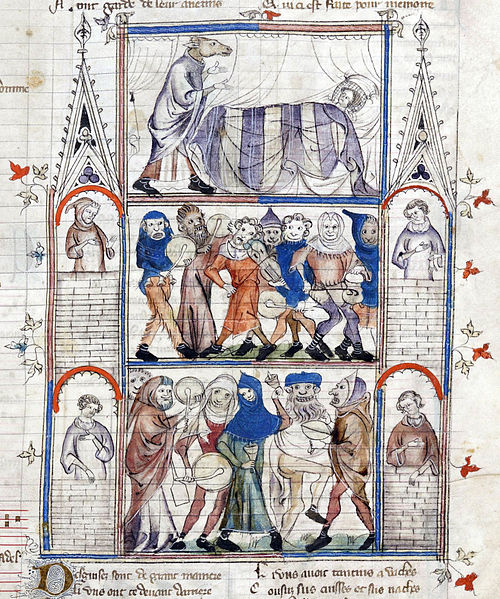

Wearing masks and armed with pots, pans, tambourines, rattles, horns and other objects that make noise, the groups of young men would walk up to the house of the “offender”, and refuse to leave unless the victim paid a fine, or did something to satisfy the youths. We know very little about the songs or verses used, but we do have an idea about what it looked like, because charivaris appear in medieval art.

The Stag Hunt

In cases of double adultery, where both lovers were married to other people, the group could stage a “stag hunt”. A man would dress up as a stag and be chased around town by other men who were dressed as hounds. Eventually, the stag would be captured and “killed off” in front of the offender’s door, spraying it with oxblood.

A theatrical execution, with oxblood as both symbol and sentence, this particularly dramatic event was also a ritual of ostracisation: it was clear, after the door was painted in blood, that the person living there was no longer welcome in the community.

The Church, predictably, tried to condemn the practice. Three synodal statutes, in 1404, 1421 and 1470, condemned the charivari in southern France. The reason was political rather than religious: in condemning marriages that the Church approves, youth groups that organised the charivari were essentially overshadowing church authority. And if you think that this was exclusive to the lower classes, let me correct you: Lucrezia Borgia and her third husband didn’t dare leave their room on the day after their wedding, for fear of how brutal the mocking would be.

Echoes of Misrule

As centuries passed and people gathered more and more in the cities, these youth groups were transformed into groups of merchants, craftsmen and professionals. Still in charge of festivals and celebrations, they carried out charivaris well into the seventeenth century. And, of course, sometimes the charivari became political, but that’s a (very interesting) story for another time.

And this is how misrule was used to enforce the rule. The humour in charivari is derisive, mocking, often violent. Vielle carcasse, folle d’amour (old carcass, crazy with love) mocked the revellers the widow getting remarried, and male impotence due to older age was not spared, either. We know of at least one occasion when someone was killed.

These days, most of us aren’t chasing stags or rattling bones outside the homes of second brides. But we still use humour to police behaviour and sexuality. We still disguise social control as comedy. And we still make noise — digital, verbal, you name it— when people break the rules of “respectability”.

There’s still oxblood on the door.

Suggested reading

Natalie Zemon Davis, Society and Culture in Early Modern France (Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press, 1977)

Robert Wheaton (ed.), Family and Sexuality in French History (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1980)

Edward Muir, Ritual in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge University Press, 2005)

Leave a comment